Intro

Open any news outlet and you will likely find stories of conflict—from full-scale wars to economic standoffs between nations. At the same time, we are launching satellites into orbit, creating Artificial Intelligences once thought to be science fiction, and making breakthroughs that defy imagination.

On one hand, we are progressing faster than ever. On the other, we seem to be regressing into tribalism and violence, repeating the same primitive behaviors we once believed humanity had outgrown.

This stark contrast leaves many of us puzzled. How can such opposing realities exist side by side? What are the root causes that sustain this paradox?

This section revisits and builds upon themes first explored in my earlier book, Patent Dystopia. That work examined how patents strangled job creation, the economy and innovation, but also touched on deeper historical and systemic parallels between business and war—particularly how both rely on competition as a necessary force for job creation and innovation.

Here, we expand that argument and explore how the failure to maintain open and fair competition leads not only to stagnation but to war itself.

Similarities Between Business and War

Business and war share a core purpose: they both compete for resources.

Businesses compete through creation, particularly in a true free market (without patents): by selling products and services in exchange for money, which they can then use to acquire the resources they want.

War competes through destruction: by threatening or causing damage to force others to surrender the resources they control.

Because the competitive dynamics of business and war are structurally similar, they also share many parallels in how they create jobs. This holds not just at a high level, but in the mechanisms of operation and resource mobilization:

- In war: When a new enemy appears, governments always find funds for bombs and warplanes—even if they previously claimed no budget for essentials like schools or hospitals. This surge of activity creates many jobs and worker bargaining power.

In business: When a serious competitor emerges, companies suddenly find funds for R&D, offer raises to retain key staff, and invest heavily in marketing—even if they had just claimed they could not afford cost-of-living increases. This surge of activity creates many jobs and worker bargaining power. - In war: Governments employ intelligence officers to gather information, craft strategies, spread propaganda, and attempt to turn enemy operatives. This generates jobs and worker bargaining power.

In business: Companies hire marketing teams, strategy analysts, and recruiters to gather competitive intelligence and win market share. This generates jobs and worker bargaining power. - In war: Soldiers serve as the tip of the spear, pushing into enemy territory to achieve victory. This generates jobs and worker bargaining power.

In business: Sales teams, PR professionals, and brand evangelists act as the spearhead in competitive markets, pushing to expand market share. This generates jobs and worker bargaining power. - In war: Engineers and scientists develop new technologies to outmatch the enemy. This generates jobs and worker bargaining power.

In business: Engineers and scientists innovate to outpace competitors. This generates jobs and worker bargaining power. - In war: Enemy attacks destroy assets like roads, bridges, and aircraft—creating a need for cleanup and rebuilding. This generates jobs and worker bargaining power.

In business: Competitors' innovations render products, tools, or strategies obsolete—creating a need for replacement and reinvention. This generates jobs and worker bargaining power.

These parallels are no coincidence. Both business and war create jobs and worker bargaining power by embracing competition without patent barriers. They ignore monopolies and oligopolies, and in doing so, unleash innovation and economic dynamism. We will soon explore historical examples that show this dynamic in action.

The Need for Competition, in One Form or Another

Here are our key theories:

1) A lack of business competition encourages military conflict. The chain reaction looks like this: a weak job market leads to fewer and lower-paying jobs, which creates economic stress and social frustration. A stressed population becomes more vulnerable to demagogues, extreme ideologies, and emotional overreactions. The outcome is often conflict—ranging from civil unrest to full-scale war.

This connection is not new. The French economist Frédéric Bastiat once captured the idea simply: “When goods do not cross borders, soldiers will.”

2) A broken economy and job market is largely the result of a the patent system. Patents allow dominant companies to form oligopolies by preemptively claiming rights to useful technologies. They build massive portfolios, not to innovate, but to block competition. This strategy systematically destroys small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which make up 99% of businesses and 60% of employment in OECD countries.

This is the core thesis of my earlier book, Patent Dystopia.

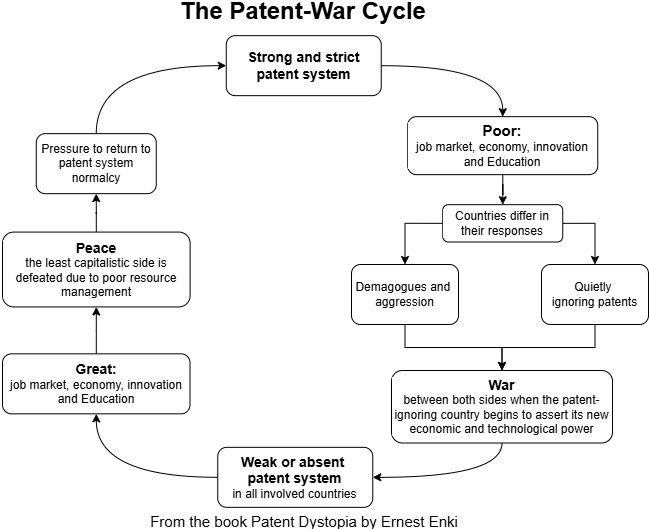

3) Modern history shows a recurring pattern—a cycle of patents and war that has gone largely unnoticed:

The Patent-War Cycle Explained

- Patents weaken the economy: A strong and strictly enforced patent system undermines innovation, weakens the job market and economy, and blocks individuals and companies from gaining Education.

- Countries differ in their responses:

- Some countries—usually a minority—begin quietly ignoring patents to accelerate their economies and allow key industries to grow.

- Others, often the leading powers, stick with the status quo. Their populations suffer increasing economic stress and begin leaning toward demagogues, extreme views and aggression—across all levels of society, from individual behavior to governmental decisions.

- War breaks out: The patent-ignoring country, economically and technologically thriving, begins to assert its new power against rivals. This leads to war between the two sides.

- Sometimes these challengers are righteous (like the early United States), other times tyrannical (like Nazi Germany). The common factor is not ideology—but the use of open innovation to gain power.

- Patents are abandoned in wartime: All parties openly drop patent enforcement to accelerate the development of weapons, machines, and production capacity.

- Innovation and job creation surge: Rapid job creation, innovation and Education take place across industries, as economies shift into high gear. Unfortunately this gives credibility to demagogues.

- Peace: One side wins—often the one with more economic freedom, which granted them better resource management. Peace is restored.

- Return to “normal”: Society pushes to reinstate order and return to normalcy, including the reestablishment of strong and strict patent systems.

- The cycle begins again.

This cycle does not apply to every conflict or period in exact terms, but it is a recognizable pattern across major global developments. As Mark Twain put it: “History does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

Let us now examine how this cycle has played out in the past.

Background: The Origins of the Patent System

The modern concept of systematic patent law can be traced back to 1474 in Venice. Patents were not awarded to original inventors, but to introducers of technologies—those who brought new crafts and techniques into a city-state.

This was a practical policy. To convince skilled artisans to relocate, city governments needed to offer strong incentives. Migration was risky—plagued by wars, poor roads, high transport costs, and the challenges of setting up business in a new place with different language and customs. Patents gave these artisans a temporary monopoly as compensation for those risks.

As Venetian artisans emigrated, they sought similar protections in their new homes. This led to the diffusion of patent systems across Europe.

This introducer-based model created a lot of room for competition. Each city-state issued its own patents to local introducers, and only if they thought the invention wouldn't naturally arrive quickly enough, allowing knowledge and skills to spread through the region. This is in sharp contrast to today’s global patent system, where protection is given to the original inventor and enforced across international borders—often with indefinite monopoly power through legal strategies like evergreening or chained patents.

Patents for introducers remained dominant for most of patent history, lasting through the First (1750–1840) and Second (1870–1914) Industrial Revolutions.

In the mid-1800s, patents faced growing criticism. The Netherlands went so far as to abolish its national patent system from 1869 to 1912—a span of 43 years—believing others would follow. Switzerland refused to adopt a national patent system until 1888 and did not allow chemical patents until 1907. Both countries did well during the Industrial Revolutions and gave rise to companies that would later succeed on the global stage. For a deeper look at this period, the book Industrialization Without National Patents by Eric Schiff is highly recommended.

For a time, the anti-patent movement was gaining ground. But when the Long Depression hit (1873–1899), free market ideas lost favor, and protectionism took hold. Support for national patent systems grew. As a compromise, patent critics accepted a system with one key safeguard: compulsory licensing. Governments could step in if a patent was unused, prices were too high, or supply was too limited—especially during emergencies. Over time, however, this safeguard was quietly eroded through international treaties. Today, compulsory licensing is rarely used.

Introducer patents were only replaced—at least in theory—by the principle of protection for the "original inventor" (even if attribution is difficult) with the signing of the 1883 Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property. This was the first global patent treaty, signed by more than 180 countries. The agreement remains in force today, with many amendedments.

In practice, however, some countries continued to ignore international patents well into the 20th century. They used foreign innovations freely to grow their own industries and job markets, as we will see in the next sections.

Even during the era of introducer patents (we could generously consider 1474-1883), we can observe a trend: a gradual decline in competition as patent jurisdictions grew larger. What began as city-states granting local patents, evolved into national patent systems. This shift concentrated control, reduced competitive pressure, and laid the groundwork for the monopolistic patent regimes we see today.

The First Patent-War Cycle: The Rise of the United States

Our first case study: the rise of the United States as an economic and technological superpower.

This section draws heavily from the book Trade Secrets: Intellectual Piracy and the Origins of American Industrial Power by Doron S. Ben-Atar, which is highly recommended reading.

Up to and during the Industrial Revolution, European powers routinely stole technologies from one another. England, as the most industrially advanced nation of the era, was frequently the primary target of this technological piracy. In response, and to protect its economic lead, England developed a centralized national patent system and attempted to enforce it across its global territories—including the American colonies.

However, the original thirteen American colonies had their own decentralized introducer-style patent systems. These systems were weakly enforced, colonial governments lacked the capacity—and often the will—to uphold any patent law, especially across the Atlantic. This gave local American industry a massive advantage: they were free to copy, adapt, and compete without the constraints that limited their British counterparts.

This openness to innovation and competition directly fueled the economic rise of the American colonies. A climate of free-market invention and job creation attracted waves of migrants from the British Isles, drawn by the promise of opportunity. Many of these migrants were skilled specialists who brought with them not their valuable Education, but in some cases pirated machinery and trade secrets, worsening the brain drain from Britain and accelerating the colonies’ industrial growth.

Over time, this economic strength enabled the loosely unified American states to build a more capable national government—one increasingly able to resist Britain’s overreach, including unfair and disproportionate taxation. As the colonies grew more confident and self-reliant, Britain attempted to reassert control—culminating in war. But this move backfired economically.

Outside of the wars against Britain—including the Revolutionary War (1775–1783) and the so-called Second American War of Independence (1812–1815)—the United States at least paid lip service to British patent claims. But once Britain became a declared enemy, all such pretense vanished. British patents were openly and entirely ignored, unleashing a new wave of American innovation, accelerating industrial development, and generating massive job creation. This period demonstrated clearly how removing patent barriers during conflict can supercharge a nation’s economic engine.

What makes the American case unique is that patent piracy was that all levels of American society took part in patent piracy, especially against the British:

- Individuals traveled to Britain to steal industrial secrets and return home to build factories.

- Cities offered incentives to european specialists to emigrate—often encouraging them to bring blueprints, know-how, and physical machinery.

- Industrialists and Societies funded mass migrations of skilled workers.

- The federal government itself organized campaigns to lure European talent and know-how to the United States.

This effort even involved many of America’s Founding Fathers and national leaders, who personally supported and facilitated patent piracy as a strategy for national growth and independence from Britain.

A striking example of American patent piracy was Samuel Slater, an Englishman who arrived in New York in 1789. As a former apprentice to a pioneer in Britain’s textile industry, Slater had memorized the designs of British textile machinery—technology that was protected by patents and subject to export bans under British law.

Upon arriving in the United States, Slater used this knowledge to build the first successful U.S. textile mill, effectively jump-starting America’s industrial revolution by infringing on British patents. For this act, he was later praised by the US President Andrew Jackson as the "Father of the American Industrial Revolution". In contrast, British authorities branded him "Slater the Traitor".

America’s embrace of foreign inventions—regardless of its legal status—was no accident. It was openly encouraged at the highest levels of government. In his very first annual address to Congress in 1790, President George Washington made the following statement:

The advancement of Agriculture, commerce and Manufactures, by all proper means, will not, I trust, need recommendation. But I cannot forbear intimating to you the expediency of giving effectual encouragement as well to the introduction of new and useful inventions from abroad, as to the exertions of skill and genius in producing them at home

Alexander Hamilton, one of America’s Founding Fathers and the first Secretary of the Treasury, was one of the main promoters of the use of foreign technology to boost domestic industry. In his 1791 Report on the Subject of Manufactures to Congress, Hamilton stated his support for:

The encouragement of new inventions and discoveries, at home, and of the introduction into the United States of such as may have been made in other countries; particularly those, which relate to machinery. …

But it it is desireable in regard to improvements and secrets of extraordinary value, to be able to extend the same benefit to Introducers, as well as Authors and Inventors; a policy which has been practiced with advantage in other countries. …

Let these Commissioners be empowered to apply the fund confided to them—to defray [pay] the expences of the emigration of Artists, and Manufacturers in particular branches of extraordinary importance—to induce the prosecution and introduction of useful discoveries, inventions and

improvements, by proportionate rewards

American newspapers and books played a key role in spreading European inventions—not to respect them, but to teach Americans how to copy them. These publications acted as tools of open technological piracy, making foreign techniques accessible to local craftsmen and entrepreneurs.

One emblematic example is the appropriately named book "One Thousand Valuable Secrets, in the Elegant and Useful Arts, Collected From the Practice of the Best Artists, and Containing an Account of the Various Methods of Engraving", published in 1795. This manual was unapologetic in its purpose. It explicitly stated:

Whilst the inhabitants of Europe are distracted by the din of arms [war], and their principal employment is to contrive the most expeditious means of destroying one another, let the happy citizens of these infant States turn their attention to the useful and elegant arts of peace; - let them avail

themselves of the discoveries of these ancient nations in the happier years that are past; until we no longer stand in need of their supplies, or remain exposed to the fluctuations of their fortune.

The work now offered to the public is well calculated to promote this beneficial purpose, being a large and various collection of important secrets in the finer arts and trades; secrets which have resulted from repeated experiments made by the first artists in England, France, Italy and

Germany, and which open an extensive field for the exercise of American ingenuity and improvement

Eventually, Britain was forced to make peace and formally accept American independence—not only because of military setbacks, but also because the United States became an industrial powerhouse, and as such could become a powerful geopolitical ally. More urgent threats were emerging in Europe, particularly the rise of the Holy Alliance and the shifting balance of power on the continent.

In summary, strict patent enforcement in Britain and lax enforcement in America allowed the United States to rapidly build its industrial base, stimulate economic prosperity, and ultimately gain the strength to confront Britain economically, and later, militarily. By leveraging unrestricted access to foreign technology, the U.S. transformed from a group of loosely connected colonies into an emerging industrial power.

The Second Patent-War Cycle: The rise of the Nazi

After World War I (1914-1918), Germany began slowly rebuilding its economy. However, this fragile recovery was upended by the Great Depression (1929–1939), which triggered a global economic collapse. As nations scrambled to recover, many turned to protectionist policies—further disrupting international trade and deepening the crisis.

Most historians agree that the prolonged economic devastation created by the Great Depression played a major role in the rise of the Nazi Party. What is less widely known is that strict patent enforcement played a significant factor in worsening it.

This concern was well articulated by Thurman Wesley Arnold, Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Antitrust Division under US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, serving from 1938 to 1943. In his own words:

The latest and today the most extensively used instrument of monopoly control is the patent privilege ...

Where necessities are involved, there is no brake on this tendency, and exploitation by patent control is most effective in necessities like housing, fuel, drugs, and basic materials

Arnold’s investigations revealed that:

- Companies across many industries were using patents to keep competitors at bay and enforce obedience from partner firms—even while holding questionable patents. Fear of legal retaliation discouraged any challenges.

- Patents were used to artificially raise the cost of essential goods. These inflated input costs rippled through the economy, damaging industries and harming individuals, especially the poor.

- Some German companies were using U.S. patents strategically. For example, they used American legal protections to raise the price of cutting-edge technologies such as tungsten carbide (second in hardness only to diamond), restricting access to these technologies in the United States while making them cheaply available in Germany.

This last point may have been a deliberate attempt to slow down technological adoption in rival nations, while enabling Nazi rearmament at home. By the time the U.S. entered World War II, it lacked the industrial ecosystem and trained workforce to take full advantage of these advanced technologies—largely because access to them had been choked off through patents.

The implications for national security are serious: historically and even today, patents can be weaponized against entire nations—used to delay technological adoption, restrict access to critical inventions, and undermine industrial development.

Hitler’s rise was fueled in large part by fixing Germany’s job market—not through free markets, but through aggressive rearmament. The Nazi regime openly ignored foreign patents to accelerate the development of advanced weaponry, machinery, and industrial capacity. This gave Germany a significant technological and economic edge over its rivals, emboldening Hitler to invade Poland in 1939, triggering World War II.

To fight Hitler effectively, Allied powers such as the United States and Britain were forced to abandon their own patent systems. Innovation and production needed to accelerate rapidly—and that meant removing legal roadblocks.

In the U.S., this was accomplished through Section 1498 of Title 28 of the U.S. Code. This statute allows the federal government—and by extension its employees, contractors, and subcontractors— the legal authority to use any patented technology without worrying about licensing, royalties, infringement lawsuits, or court injunctions. Many countries have similar laws to enable them to ignore patents during times of war. This allowed American industry to catch up technologically and ultimately defeat the Axis powers.

Ignoring patents also had an unexpected benefit: millions of people received both formal and experiential Education in cutting-edge technologies as part of the war effort.

When the war ended, these workers transitioned into the private sector, applying their Education to businesses and spark economic growth. This created the Golden Age (50s and 60s) in the United States, Britain, and even in some former Axis countries like Italy.

The result was a thriving job market where the average citizen could afford to raise a family, buy a home, and begin fighting for civil rights and social progress—laying the foundation for many of the laws, institutions, and traditions that shape the modern world.

However, strict patent enforcment returned post war, and as the knowledge of older tehcnologies were no longer useful as time passed, and newer tehcnologies were blocked by patents, this Golden Age ended around the late 60s and early 70s.

This shift led to a now-infamous phenomenon: the productivity paradox—worker productivity continued to rise, but real wages stagnated. This began many social and economic challenges that persist to this day; many of them are explored and documented on the website WTF Happened in 1971?

In summary, strict patent enforcement in the US and Europe and lax enforcement in Germany allowed the Nazis to rapidly build its industrial base, stimulate economic prosperity, and ultimately gain the strength to intimidate and overpower other nations. The Allied nations were only able to defeat them by abandoning patent enforcement themselves, unleashing a wave of innovation and industrial production that allowed them to catch up technologically and stand a fighting chance.

The Third Patent-War Cycle: The rise of the Soviet Union

The rise of the Soviet Union as a technological superpower surprised much of the world. How could a nation without price signals, free markets, or private enterprise outperform capitalist countries in some of the most complex engineering and construction feats in history?

The shock was global when the USSR launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, into orbit in October 1957. That achievement was followed by a string of historic milestones, including sending the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into space in April 1961. These victories forced Western powers to question how a centrally planned economy could pull so far ahead—at least temporarily—in the space and military technology race.

One critical factor is often overlooked: the Soviet Union had basically abolished patents. Their leadership viewed patents as tools of capitalist exploitation—part of a system they sought to dismantle. Ironically, this ideological stance freed their economy from the very restrictions that continued to bind Western innovation. By removing legal barriers to technology sharing and adaptation, the Soviets unlocked fast-paced industrial replication and improvement.

It is true that a tyrannical regime can divert massive resources to state projects in ways that democratic societies typically cannot. But that alone does not explain the Soviet advantage in the early years of the space race. Even after the U.S. began taking the competition seriously and ramped up spending, the USSR remained a strong competitor—longer than their inefficient economic model should have allowed.

The cycle repeated itself when the United States decided to take the space race seriously. In response to Soviet achievements, the U.S. government poured vast resources into NASA. What is rarely mentioned in history books is that NASA operates under the protection of Section 1498, which allowed the agency to freely use any patented technology without needing to identify patent holders, negotiate licensing agreements, pay royalties or worry about injunctions.

In essence, NASA did what the Soviets had been doing all along: ignoring patents and focusing entirely on solving problems. The result was an explosion of innovation, economic activity, and job creation.

Just the Apollo Program—aimed at landing a person on the Moon between 1968 and 1972—employed approximately 400,000 people at its peak. This included engineers, scientists, mathematicians, technicians, astronauts, administrators, support staff, and contractors spread across NASA and numerous partner companies. The technological output was extraordinary. The program directly or indirectly led to groundbreaking innovations such as:

- Portable defibrillators

- Computed Axial Tomography (CAT) scans

- Water purification systems

- Microprocessors

- Global Positioning System (GPS)

- Heat-resistant and fire-resistant materials

- Memory foam

- Breathing masks

- LED lighting

- Improved baby formula

- The Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET), which would later evolve into the modern internet

Besides the space race, the U.S. government also leveraged its World War II strategy of funding university-led research and allowing private companies to freely commercialize the results—especially for military applications. A key hub in this system was Stanford University, under the leadership of Frederick Terman.

This model laid the foundations of what would later become known as Silicon Valley: a military-industrial-university complex that carried out extensive, often classified, work for the U.S. government. Patent barriers were effectively ignored, enabling researchers and companies to focus entirely on solving hard problems. The result was a surge of technological innovation and a thriving economic ecosystem.

The later invention of the transistor and the rise of the computer industry did not create Silicon Valley—they simply took advantage of the industrial infrastructure and culture that had already been built through military and academic collaboration.

Entrepreneur and history lover Steve Blank has documented this little-known origin in his excellent blog series The Secret History of Silicon Valley, which is highly recommended reading.

Ultimately, it was not just the missiles or astronauts that defeated the Soviet Union. It was the combined innovation of NASA and Silicon Valley—a decentralized, largely patent-free ecosystem of talent, experimentation, and rapid learning that the Soviet system could not replicate.

However, this particular loop of the patent-war cycle produced an important and often overlooked side effect. During the Cold War, the world anticipated a potential World War III between the United States and the Soviet Union. As a result, many countries prepared for two key scenarios:

- Armed conflict that they could be forced to participate in

- Trade disruption, especially through blockades or the collapse of global shipping and supply chains

To prepare, governments maintained large, modernized military forces and often nationalized or tightly regulated key industries such as oil, steel, and telecommunications to ensure strategic independence. These efforts required close collaboration with national governments—an environment where patents were often ignored in the name of sovereignty and national security.

The United States, while officially committed to patent protection, could not strongly enforce international patent rights in this climate. Pushing too hard on allies to respect U.S. or Western patents risked driving them into closer alignment with the Soviet bloc.

This led to a period of tacit U.S. tolerance of patent piracy, especially in countries that had geopolitical value in the Cold War rivalry. These included:

- South Korea, recovering from the Korean War, positioned as a capitalist counterpoint to North Korea

- Japan, rebuilding after World War II and located dangerously close to Soviet territory

- Taiwan and Hong Kong, both flooded with refugees from Communist China and meant to showcase the strengths of market economies

In these key nations, patent piracy was not only tolerated—it was encouraged by their goverments- often under euphemisms like "copying" or "reverse engineering." This freedom to build upon foreign technologies without legal barriers fueled rapid industrial growth and innovation.

This is the true reason why only these countries—unlike the rest of the post-war world—successfully transitioned into stable, developed economies. It was not simply cultural work ethic or good governance. It was because, for a critical window of time, they were allowed to innovate without the restrictions of the global patent regime.

However, with the fall of the Soviet Union in December 1991, the common geopolitical enemy was defeated. This shifted the balance of power. The United States, along with developed European nations—who had once thrived through ignoring patents themselves—began to aggressively promote stronger and strict global patent enforcement.

This push was embedded within a broader package of neoliberal reforms known as the Washington Consensus. These reforms included many valuable goals such as reducing bureaucracy, stabilizing economies, and increasing market competition. But they also contained a hidden trojan horse, the sweeping expansion and hardening of global patent system:

- Expansion of patentable subject matter—including software, genetic material, and business methods

- Lengthened patent durations in many countries, often well beyond historical norms

- Mandatory strict legal frameworks for enforcing patent rights

- Severe restrictions on compulsory licensing, once a key tool for governments to protect public interest

The most powerful instrument of this agenda was the 1994 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), enforced through the World Trade Organization. TRIPS effectively forced developing countries to implement strict patent laws under threat of trade sanctions.

Since the TRIPS agreement and other patent related treaties, many countries have experienced slower growth, rising inequality, and increasing industry consolidation into oligopolies of foreign companies leveraging their massive patent portfolios. Patents became not tools of innovation, but weapons of market control, allowing dominant firms to entrench their power and crush competition.

While some claim that today’s patent system has been with us for centuries, that is misleading. The current model—with global scope, long duration, strict enforcement, and negligible use of compulsory licenses—only emerged after 1991. It is a recent construction, born from post–Cold War politics, not historical tradition.

In fact, for most of modern history, the true tradition has been weak patents, limited enforcement, or no patent system at all—especially during key historical moments of technological progress, economic recovery, and job creation.

In summary, strict patent enforcement in the United States and the absence of patent restrictions in the Soviet Union allowed the Soviets to rapidly build their industrial base and gain the strength to intimidate and challenge other nations—despite the inherent flaws of their planned economy. The United States was only able to defeat them by abandoning patent enforcement themselves. This shift unleashed a surge of innovation and industrial production—most notably in Silicon Valley and NASA—which enabled the U.S. to catch up technologically and ultimately outcompete the Soviet Union. However the their fall enabled the United States and western allies (who became powerful via their earlier patent piracy) to push for most of the world to stonger and stricter patent systems.

The Fourth Patent-War Cycle: The rise of the Modern China

With the United States emerging from the Cold War as the sole military, economic, and technological superpower, no nation dared to challenge its push for strict global patent enforcement. That is, except for the one country large and independent enough to chart its own course: China.

China embarked on an ambitious program of modernization and integration into the global economy, including joining the World Trade Organization in 2001. But China’s path to technological advancement followed a familiar pattern — the same path once taken by Britain and the United States during the Industrial Revolution, and by South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Hong Kong during the Cold War.

That path was built on widespread patent piracy. By allowing companies and individuals to copy and learn from foreign technologies without the burden of licensing fees or legal risks, China created space for its industries to grow independently. This allowed its firms to avoid dependence on foreign multinationals holding vast and overlapping patent portfolios across nearly every conceivable sector.

Initially, much of this development came through offshoring—as Western firms relocated manufacturing to China. But over time, this evolved into imitation, as Chinese firms gained hands-on experience (experiential Education) with production. Eventually, that imitation matured into genuine innovation.

Interestingly, in many ways, Chinese patent piracy is quite literally helping to save the world. While often criticized, its practical consequences have produced tangible global benefits—particularly in areas where Western economies are stagnating under the weight of oligopolies and patent barriers.

Here are three key ways this dynamic plays out:

- Relief from global inflation. Many industries around the world are dominated by oligopolies backed by massive patent portfolios. These firms often exploit their lack of competition by increasing prices while reducing product quality or quantity. Governments, in turn, attempt to fix their economy with monetary expansion, contributing to persistent inflation. But China’s internal markets remain highly competitive, in part because widespread patent litigation is not used to drive firms out of business. As a result, Chinese firms produce and export vast quantities of affordable goods, providing critical cost relief to the global middle and working classes.

- Acceleration of green technology. While many wealthy nations have made only symbolic gestures toward fighting climate change, useful innovation is often blocked by patent disputes. Dominant firms with vested interests frequently hold key patents that prevent or delay the deployment of disruptive green technologies. Meanwhile, oil-rich regimes—many with poor human rights records—gain wealth and geopolitical power by supplying energy to a dependent world. Fortunately, China’s willingness to ignore restrictive patents has enabled the mass production of green technologies like solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, electric vehicles, and high-speed rail systems. These technologies are now world-class, providing an alternative path that helps address both climate change and geopolitical dependence on autocracies.

- Revitalization of innovation and job creation. Innovation is a critical engine of job creation. In a healthy market, companies are forced to innovate and keep pace with their competitors, and hiring is absolutely necessary for that. However, in patent-protected oligopolies, firms often suppress disruptive technologies to protect outdated infrastructure and maximize profit. This is not capitalism—it is oligopoly / crony capitalism based on patent legal privileges. China’s competitive industries, such as smartphones, cars and televisions, have injected much-needed pressure into stagnant Western markets, forcing incumbent firms to innovate and compete. This has led to real job creation and has helped soften the crisis of disappearing middle-class employment in the West.

It is important to recognize that China’s approach is not driven by altruism. Much like Adam Smith’s famous baker, China acts in its own self-interest. Its strategy of rapid industrialization—based in large part on ignoring foreign patents—has produced extraordinary results. By leveraging this approach, China has lifted nearly 800 million people out of extreme poverty, accounting for approximately 75% of the global reduction in poverty over the past few decades.

However, this economic success comes with serious caveats. China’s record on minority rights and civil liberties remains deeply problematic. As China grows more powerful, it has also grown more assertive geopolitically—while much of the rest of the world struggles with stagnation, inequality, and political instability. In many countries, this is fueling the rise of demagogues and extreme ideologies.

These conditions—an aggressive rising power on one side and weakened polarized societies on the other—are once again stirring talks of a major war. Fortunately, we are not there yet. We still have a chance to break the cycle that has defined modern history: the Patent-War cycle.

If the global community were to abolish the patent system, the results could be transformative. SMEs would flourish, unburdened by threats of litigation. Large companies would be forced to unleash all the technologies they have been suppressing and flood global markets with useful products and services, to proactively prevent competitors from doing it first.

This would lead to factories and offices opening across diverse regions, and competition would drive down prices while improving quality. The result would be a massive surge in job creation, helping the global economy stabilize and reducing the appeal of demagogues and extreme ideologies.

More importantly, innovation and economic prosperity would no longer be exclusive to countries willing to disregard patents, and unfortuantely also disregard human rights. Instead, ethical and reputable producers everywhere could compete on equal footing. This shift would weaken the monopoly power of authoritarian regimes and strengthen the moral and economic influence of open societies. Over time, it could even pressure abusive governments to reform from within.

Conclusion

The rise and fall of the patent system has shaped much of modern history. By understanding the Patent-War cycle, we gain the power to break it—and pave the way for a more stable and prosperous future. The path forward is clear: free and open competition can unleash massive job creation, accelerate innovation, and help us build a resilient, equitable global economy.

Here is another way to see it: a bad job market will eventually lead to social disruption. That disruption is resolved—either voluntarily or violently—by ignoring patents until the job market heals.

In the end, we have only two options:

- Abolish patents during peacetime, allowing businesses to compete freely, fueling innovation and job creation through healthy market dynamics.

- Ignore patents during wartime, as militaries scramble to innovate and produce freely under existential pressure—again triggering job creation and economic growth, but at a much higher cost.

Ignoring patents is not optional. The only real choice is when—and at what cost—we choose to do it.

In my book Patent Dystopia, we examine how innovation often thrives without patents. History offers many examples—well beyond times of war—where innovation thrived in open, competitive environments.

After abolishing patents, if governments really believe incentives are necessary in certain areas, prizes can offer a far better alternative to patents. Even non-monetary rewards, such as public recognition or status, can be meaningful incentives.

Other tools—like tax deductions and direct public investment—also support invention without the downsides of monopolies. These approaches encourage innovation while keeping markets open and competitive.

The path forward is clear. With the right ideas and tools in hand, what matters now is execution.